Wildlife Research and Management Pty Ltd

The Western Barred Bandicoot (Perameles bougainville)

The Western Barred Bandicoot, once quaintly known as "Bougainville’s pouched-badger",

was first recorded on the voyage of the French ship Uranie to Shark Bay in Western

Australia in 1817. They were collected on Peron Peninsula and were quite "common".

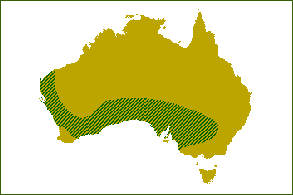

At this time, they were widespread across Australia through the southern arid zone,

from the Liverpool Plains i n New South Wales to the north-west coast of Western Australia.

The last specimen recorded from the Australian mainland was collected at Rawlinna

in Western Australia in 1929. They have probably been extinct on mainland Australia

for at least 60 years; and so survived a mere 120 years after their discovery by

Europeans.

n New South Wales to the north-west coast of Western Australia.

The last specimen recorded from the Australian mainland was collected at Rawlinna

in Western Australia in 1929. They have probably been extinct on mainland Australia

for at least 60 years; and so survived a mere 120 years after their discovery by

Europeans.

The Western Barred Bandicoot is one of the long-nosed bandicoots and is the smallest member of the bandicoot family. They are more delicate than other species of bandicoot, with an adult weight to 300 grams. Their fur is long and soft and is a mottled greyish, yellow colour. They are distinguished by two or three pale fawn-coloured bars across the hind quarters.

Shaded area indicates former distribution of the western barred bandicoot

Like other members of the bandicoot family, the Western Barred Bandicoot is nocturnal, nesting each day under low shrubs in a depression beneath dense litter. Their diet is predominantly insectivorous, although they will also eat spiders, earthworms, berries, seeds, roots and small herbaceous plants as they hunt and dig for their food.

The bandicoots have a high reproductive output, which makes them excellent prospects

for reintroduction to the mainland. The gestation period of the Western Barred Bandicoot

is a mere 12.5 days (one of the shortest gestation periods recorded in mammals).

Two offspring are usually produced per litter, with new born young only 10 mm in

length and weighing about a quarter of a gram. Their breeding is concentrated in

the wetter winter and spring months, but they may also breed opportunistically throughout

the year when unseasonal rainfall promotes good conditions.

The bandicoots have a backwards opening pouch with eight nipples where young remain and suckle for approximately 45 to 60 days before venturing out into the world. The high number of nipples relative to the number of young seems to be an adaptation to having many litters in quick succession (a litter every 80 days). Pouch young of successive litters are thought to alternate teats, as the teats that have been suckled previously take approximately one month to return to a size that newborn young are capable of attaching to. By about 70 to 80 days of age the young become independent and disperse from their mother. The males have a home range of up to 14 hectares, while females range over less than 6 hectares on Dorre Island. While their home ranges overlap, each individual has a central core area that is not encroached by other bandicoots.

Researchers transferred Western Barred Bandicoots from Dorre Island to the nearby conservation reserve of Heirisson Prong at Shark Bay in 1995, to successfully re-establish the first mainland population and to provide a more secure future for the species. The most successful reintroductions of endangered mammals have been in areas where cats and foxes have been controlled or eradicated, therefore predator control is a major priority for any mainland reintroduction.

The reintroduction has been supported by the combined efforts of a mining company (Shark Bay Salt Joint Venture, now Shark Bay Resources), the local community of Useless Loop, government departments (Environment Australia and Agriculture Western Australia), and conservation organisations (Earthwatch and Australian Geographic). Other reintroductions of this species are planned and if these populations prove successful, then perhaps the status of the Western Barred Bandicoot may become sufficiently secure for it to be removed from the list of endangered species.

Adapted from Nature Australia (1997) 25:20-21.

| Project overview |

| Banksia Awards |

| Burrowing bettong |

| Western barred bandicoot |

| Sticknest rats |

| Earthwatch |

| Publications |